Front-Loading Development: Financial Architecture for Knowledge Economies

How royalty securitization, IP-backed lending, and catalogue funds can mobilize $650M in patient capital from African knowledge assets by 2030

Executive Summary

Africa’s industrialization has stalled because the capital formation mechanism assumed by standard development models never materialized. Educated workers exist. Entrepreneurial capacity exists. The formal sector jobs that convert education into savings do not.

Charlie Robertson’s industrialization framework—literacy rises, fertility drops, household savings accumulate, banks channel capital into factories, wage employment expands—works when jobs exist to absorb educated workers at wages high enough to generate investable surplus. South Korea, Vietnam, and Bangladesh validated this sequence. But Africa arrived late to global manufacturing, and the structural conditions that made the model work have shifted.

Nigeria’s literacy climbed from 51% to 62% over two decades. Per capita GDP growth averaged under 1% annually. Ghana’s literacy rose from 58% to 79%. Youth unemployment remains above 12%, underemployment exceeds 40%. Education delivered what it promised: literate workers. The downstream jobs never materialized at scale to convert that literacy into household savings.

Three constraints broke the loop: automation compressed manufacturing employment (factories that once needed 1,000 workers now need 200), supply chains consolidated in China and Southeast Asia (breaking in now requires 15-20 year capital cycles African economies can’t finance competitively), and infrastructure deficits raise per-unit costs 20-40% above Asian comparables even with lower wages.

But while waiting for factories, Africa has been generating a different class of tradable output: knowledge assets. Music catalogues now generate $60M+ annually in global streaming revenue. Nollywood produces 2,500 films yearly with expanding platform distribution. BPO and digital services exports exceed $1.4B annually. AI training data, localization services, and software development add $300-500M more. Combined, knowledge economy exports approach $1-1.5B annually—small relative to total trade, but growing 25-40% yearly and requiring 1/100th the upfront capital of manufacturing.

The strategic opportunity: use knowledge economy cashflows to generate the patient capital pools that Robertson’s model assumes must exist before industrialization begins. Those pools can’t form when wage employment doesn’t materialize. Knowledge exports can create them faster.

This requires financial architecture that captures knowledge export revenue (currently 40-60% leaks offshore to foreign intermediaries), pools it at institutional scale, and recycles it into patient capital. Four models provide that infrastructure: royalty securitization (converting future cashflows into upfront capital via bond issuance), IP-backed lending (loans collateralized by IP revenue streams), Africa-IP acquisition funds (private equity purchasing and professionalizing African IP), and creator holding company structures (enabling asset accumulation and intergenerational transfer).

If African policymakers allocated even 10% of SEZ budgets toward knowledge economy infrastructure—IP registries, licensing platforms, royalty collection rails, valuation capacity—the continent could mobilize $650M in new patient capital within five years. That capital then finances industrial projects, infrastructure development, and human capital formation with better terms than traditional FDI.

Africa still needs factories. But the capital to build them can come from monetizing what already works: music catalogues, digital services, creative IP generating dollar revenue today.

I. The Capital Formation Bottleneck

Robertson’s industrialization model remains the most empirically validated development framework we have. Literacy enables workforce productivity. Lower fertility increases household savings rates. Banks intermediate those savings into productive investment. Wage employment expands. The cycle compounds.

It worked across East Asia, Southeast Asia, and parts of Latin America because a critical dependency held: formal sector employment absorbed educated workers at wages sufficient to generate household surplus.

In Africa, that dependency is failing.

Nigeria’s literacy rate stands at approximately 62%, up from 51% in 2000. Yet GDP per capita growth has averaged under 1% annually over the same period. Ghana’s literacy climbed from 58% to 79% between 2000 and 2021. Real wage growth for urban workers has been effectively flat when adjusted for inflation. Kenya’s literacy reached 82%. Youth unemployment remains structurally high despite educational expansion.

The pattern repeats across the continent. Rising literacy without corresponding income growth points to a specific breakdown: the formal sector jobs never materialized at scale.

Why?

First constraint: Automation compression. Manufacturing jobs that once required 1,000 workers now require 200-300, with higher skill floors. Garment production—the classic entry point for industrializing economies—has seen productivity per worker increase 40-60% since 2000 through automation and process optimization. The employment multiplier that powered Asia’s rise has shrunk.

Second constraint: Supply chain consolidation. China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh absorbed the labor-intensive segments of global manufacturing between 1990 and 2015. Breaking into these supply chains now requires competing on infrastructure, logistics, and scale—not just labor costs. African manufacturers face power costs 2-3x higher than Asian comparables, logistics delays that add 15-25% to delivered costs, and financing at 28-35% when competitors access capital at 5-8%.

Third constraint: The capital requirement. Building competitive manufacturing capacity requires 15-20 year investment horizons. A mid-sized garment factory requires $80-120M in capex (land, buildings, machinery, working capital). At Nigerian lending rates of 28-35%, debt service alone consumes potential margins before operational risk is factored in. Foreign direct investment flows toward extractive sectors or services, not manufacturing.

The result: literacy is rising, but the formal sector jobs that convert education into household savings aren’t materializing fast enough.

Simple household arithmetic illustrates the bind:

Urban household income: $200-400/month (median across major cities)

Rent: 35-40% = $70-160

Food: 25-30% = $50-120

Transport: 12-15% = $24-60

Discretionary/savings potential: $56-60/month

To generate pools of capital large enough for industrial lending, African households need to save consistently at levels that current wage structures make nearly impossible. A $50M industrial project requires aggregating savings from 15,000-20,000 households over 5-7 years—assuming zero consumption shocks, stable employment, and functional banking intermediation.

This is the capital formation bottleneck. Manufacturing requires patient capital. Patient capital requires household savings. Household savings require wage employment. Wage employment requires factories already built.

Robertson’s logic holds when jobs exist to convert education into savings. But Africa can’t wait 15-20 years for that loop to close while manufacturing windows narrow and automation accelerates.

The question therefore becomes: Is there a different cashflow source that can generate investable capital faster than waiting for manufacturing employment to produce household savings?

II. Knowledge Asset Economics: The Numbers That Matter

While Africa has been waiting for factories, it has been producing a different class of tradable output: knowledge assets.

These aren’t abstract concepts. They’re revenue-generating exports with verifiable cashflows, global demand, and capital requirements 100-500x lower than manufacturing.

Music intellectual property. African artists now generate approximately $60M annually in global streaming revenue (net artist share after platform fees and label/publisher participation). This includes Afrobeats catalogues with proven commercial traction on Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube, and emerging platforms. Burna Boy’s catalogue alone generates estimated $8-12M annually. Wizkid, Tems, Davido, and dozens of mid-tier artists collectively drive the remainder.

Production costs for commercially viable releases: $5-15k per project (recording, mixing, mastering). Marketing and promotion costs (music videos, playlist pitching, digital campaigns, touring): $40-80k for serious breakthrough attempts. Total artist development capex: $50-100k per artist for professional commercial push.

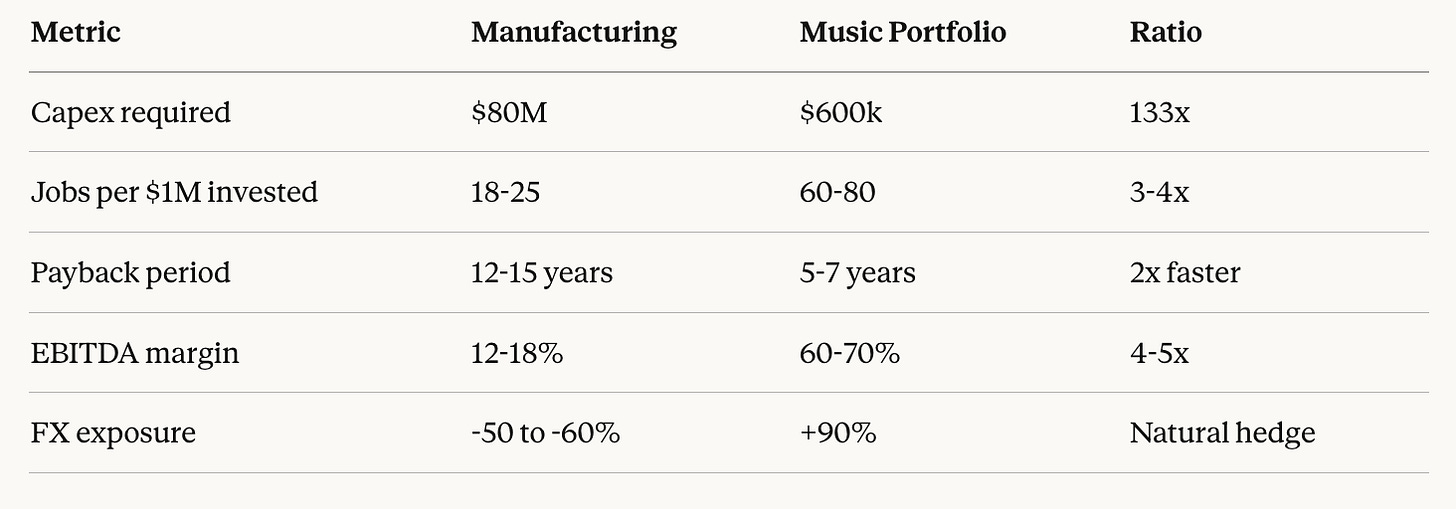

Compare this to manufacturing:

Manufacturing baseline (garment factory):

Capex: $80-120M (land, buildings, machinery, working capital)

Employment: 1,500-2,000 workers at $180-220/month average

Annual wage bill: $3.2-5.3M

Gross exports: $35-50M/year (depending on capacity utilization)

EBITDA margin: 12-18% = $4.2-9M

Payback period: 12-15 years at 28-35% cost of capital

FX exposure: Negative 50-60% (imported inputs, machinery debt service in dollars)

Failure modes: Power outages, logistics delays, demand shocks, currency crises, labor disputes

Knowledge asset baseline (music catalogue portfolio):

Capex: $600k (10 artists, mixed investment levels)

Employment: 35-50 people (artists, producers, managers, marketing teams)

Revenue outcome (Year 4-5 steady state): $235k annually

1 breakthrough artist: $150k/year

1 mid-tier catalogue: $40k/year

3 moderate performers: $15k each = $45k

5 non-commercial: minimal

EBITDA margin: 60-70% (low overhead once produced)

Payback period: 5-7 years

FX exposure: Positive 90%+ (revenue dollar-denominated, costs naira-denominated)

Failure modes: Catalogue doesn’t achieve commercial traction, platform algorithm changes, artist management conflicts

Per-dollar capital efficiency comparison:

The absolute revenue scale differs dramatically—a single factory generates more total output than a single catalogue portfolio. But the capital efficiency and risk-adjusted returns tell a different story. For every dollar deployed, knowledge assets generate faster payback, higher margins, positive FX exposure, and employment creation at comparable or better rates per unit of capital.

This pattern extends across knowledge economy sectors:

Film and television production (Nollywood model):

Production capex: $50-200k per feature film

Employment: 30-50 crew per project

Revenue potential: $100-300k lifetime (theatrical, streaming, TV rights)

Payback: 2-4 years

Annual sector exports: $100-150M

BPO and digital services:

Workstation setup: $10-30k (equipment, software, connectivity)

Employment: 1-2 workers per workstation

Revenue per workstation: $25-50k annually

Payback: 1-2 years

Kenya BPO sector alone: ~$1B annual exports

Nigeria tech services estimated: $400-600M

Software development and SaaS:

Developer setup costs: $5-15k (equipment, tools, licenses)

Revenue per developer: $40-80k annually (outsourced contracts, product revenue)

Payback: <1 year in many cases

Estimated African software exports: $300-500M annually

AI training data and localization services:

Data labeler setup: <$5k (device, connectivity, platform access)

Revenue per labeler: $8-15k annually

Payback: <1 year

Estimated current market: $50-100M, growing 40-50% annually

The strategic insight is numeric: knowledge assets generate recurring dollar-denominated cashflows within 24-36 months with capital requirements 100-500x lower than manufacturing. They don’t require 20-year infrastructure build-outs, don’t depend on global supply chain integration, and produce positive FX exposure that creates natural hedges against naira depreciation.

Knowledge exports become the logical first move — the cashflow bridge that generates patient capital pools which can then finance industrial development — with better terms than waiting for household savings to accumulate from jobs that haven’t materialized.

If Nigeria deployed $50M into knowledge economy infrastructure—less than 5% of typical annual SEZ allocations—it could catalyze $200-300M in new export revenue within 3-5 years. That revenue, if captured and recycled properly, generates the savings Robertson’s model assumes must exist before industrialization begins.

The strategic task becomes clearer: generate investable capital from what Africa already produces efficiently, then deploy it toward what still needs building.

But generating this investable capital requires capturing knowledge cashflows. And, as it stands, this is far from the case. In fact, the bulk of these cashflows evaporate before touching the continent.

Why do these cashflows currently dissipate? What is the financial architecture to capture them, and the regulatory infrastructure required to make it work? Continues online.

[Continue reading: Front-Loading Development]