Music Publishing Is Real Estate, Not Merchandise

Why Songs Outperform Sounds

Most people chase music rights like they chase hits—loud, fast, and short-lived. But the most valuable music assets aren’t the ones everyone hears. They’re the ones that keep getting licensed, reused, reinterpreted, and quietly paid for—decades after the spotlight fades.

That’s publishing.

If you could only own one part of a song—either the master recording or the underlying composition—you should choose the publishing rights almost every time. Not because they pay more today, but because they endure, compound, and scale. Publishing is IP infrastructure. Masters are content.

This isn’t about theory. It’s about rights, revenue, and long-term asset performance.

1. Publishing Is Infrastructure. Masters Are Products.

A master recording is the recorded performance—the sound file you hear on Spotify or Apple Music. It’s what gets marketed, streamed, and synched into media. It’s perishable.

Publishing, by contrast, is the legal right to the composition itself—the melody, lyrics, structure, and creative DNA of the song. It’s what underlies the master, and every cover, interpolation, or derivative use of that song in any form.

Think of it this way: the master is the house. The composition is the land underneath it.

The land lasts longer.

2. How Money Flows: The Rights Pipeline Behind a Stream

When a song is streamed on a digital service provider (DSP), two parallel rights must be licensed:

• The master recording

• The composition (publishing)

Here’s how the publishing side breaks down:

• DSPs pay out mechanical royalties (for reproducing the composition) and performance royalties (for making the composition available).

• In the U.S., mechanicals flow through The MLC, while performance royalties are routed via PROs like ASCAP or BMI.

• In other markets, usually one collection society or CMO handles both.

Publishing income from a single stream might be just cents—but those cents are routed through multiple entities, and spread across writer and publisher shares.

And like any multi-jurisdictional pipeline, this one leaks—due to bad metadata, non-registration, or poor administration.

Publishing pays best when it’s properly plumbed.

3. Why Publishing Outperforms (Even Though It Starts Smaller)

A master is front-loaded. Publishing is long-tailed.

Master income tends to spike early—streaming, sync, and sales in the first few years (from pre/post release promo runs). After that, it trails off unless re-promoted. Publishing, on the other hand, keeps earning as long as the song is used anywhere—by anyone.

That includes:

• Radio, concerts, streaming platforms

• TV, ads, film, video games (sync licensing)

• New recordings of the same song (covers, interpolations)

• Karaoke, print, educational uses

Publishing income is both linked to and independent of the original recording.

• When the original recording is played or licensed, publishing earns.

• When someone else records or performs the same song, publishing still earns.

Publishing doesn’t depend on the artist being relevant. It depends on the song being used.

And that use can come from entirely new sources over time.

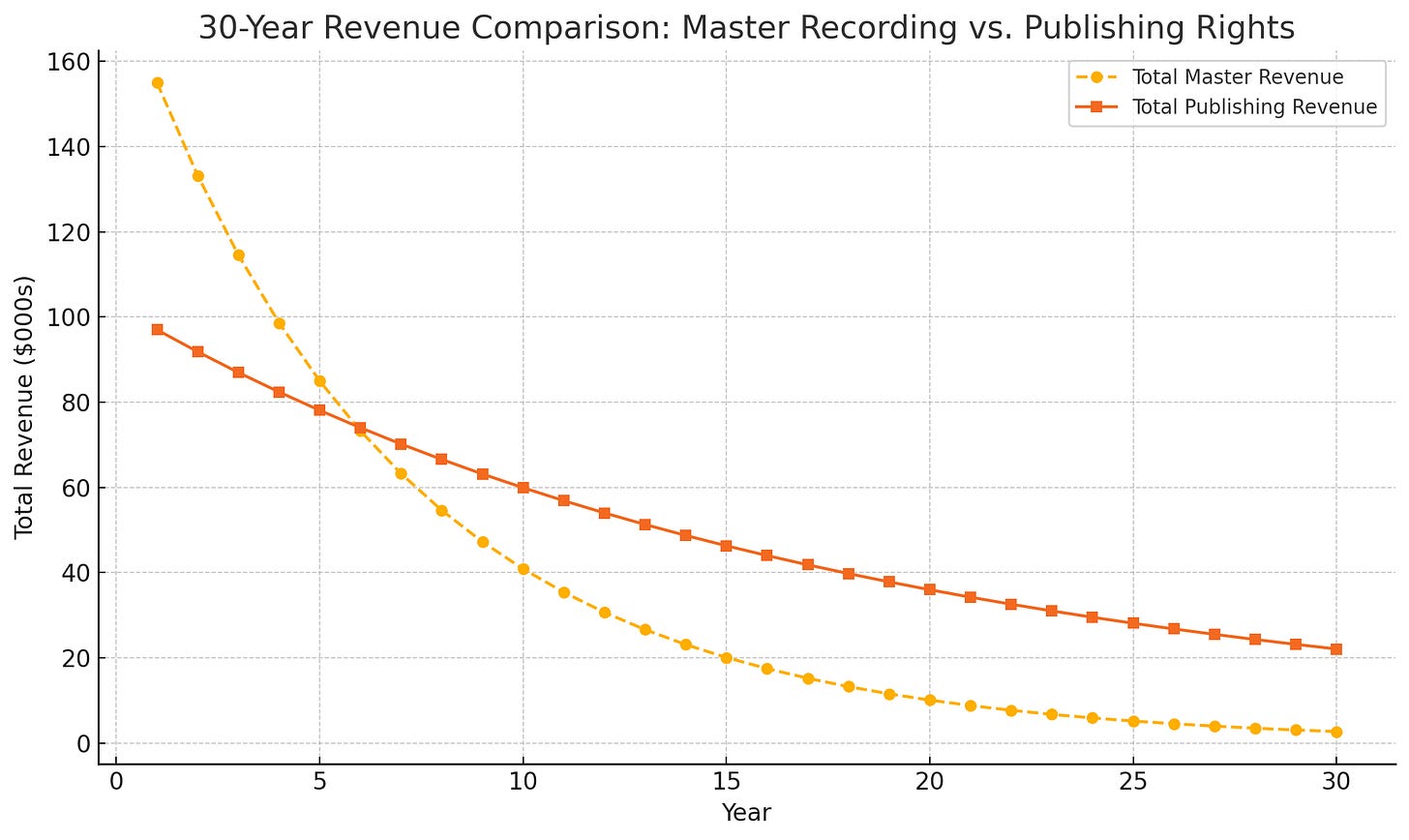

4. A 30 Year Example: Publishing Wins the Long Game

Let’s look at a moderately successful catalog track—think regional hit, steady sync performer, or evergreen digital earner.

Over a 30 year period, a master recording could, for example, generate around $1,000,000 in total revenue—most of it front-loaded in the first 5 to 7 years through streaming, sync, and sales.

In the same timeframe, the publishing rights embedded in that same recording could earn $1,500,000 or more, driven by two distinct income streams:

Tied to the original recording: performance royalties from broadcast or streaming; mechanicals from digital use; syncs of that specific master.

Independent of the recording: new cover versions, interpolations by emerging artists, karaoke, live performances, and fresh syncs of alternate recordings.

This dual pathway means publishing benefits from both artist momentum and post-hype longevity—earning long after the master fades from commercial relevance.

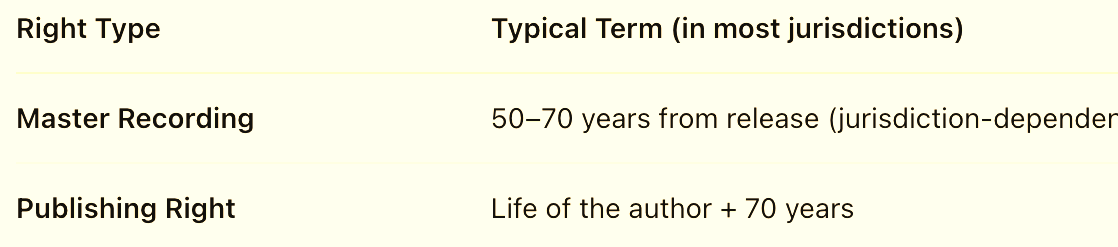

Publishing simply lives longer-both commercially and legally.

With almost double the rights term, publishing always wins out in the long run.

5. Strategic Takeaways: Rights Are Capital Assets

Who You Are + What You Should Do—

Producer/Songwriter: Retain ownership where possible. Register globally. Audit consistently.

Artist: Prioritize admin-only deals to retain control and reduce fees—unless co-pub unlocks sync/promo leverage.

Publisher: Be infrastructure, not just catalog owners. Rights management = alpha.

Investor: Publishing = non-correlated cash flow with inflation resistance and global scale.

Lawyer/Advisor: Treat publishing as you would land rights. Secure reversions, enforce metadata compliance (ie up to date “land registry” details), and protect valuation upside.

Conclusion: Own the Song, Not Just the Sound

Hits fade. Formats change. Artists move on. But a well-structured publishing right can keep paying—across decades, borders, and business models.

Publishing is not just IP. It’s capital. And in a noisy, volatile music market, it’s the quiet rights that keep compounding.