Nigeria Inc: Stop Firing CEOs. Govern the Board

Nigeria’s accountability crisis begins with a Board no one governs

Nigeria operates like a conglomerate where shareholders obsess over the Group CEO while ignoring the Board that actually controls budgets, hires management, and sets policy. The result? A republic with the power structure of a corporation but the accountability instincts of a kingdom.

Map Nigeria’s federal structure onto a corporate org chart and the dysfunction becomes obvious. The holding company micromanages subsidiaries that should be autonomous profit centers. The Board has been captured by the management it’s supposed to supervise. Shareholders fixate on firing the CEO while ignoring that most operational decisions never cross his desk. And the entire group survives on a revenue model that incentivizes dependency rather than performance.

The puzzle isn’t that Nigeria underperforms—it’s that a system this poorly designed continues to command legitimacy. The answer: Nigeria imported the organizational form of Western republicanism but retained the psychological model of indigenous monarchy. It’s a corporate governance structure operated by people looking for a king.

The Corporate Anatomy

Nigeria Holdings PLC (Federal Government) functions as the HoldCo—responsible for vision, policy coordination, and capital allocation. In well-run conglomerates, the HoldCo sets strategy and holds subsidiaries accountable; it doesn’t operate businesses directly.

Nigeria’s HoldCo does the opposite. It monopolizes revenue through centralized oil receipts and VAT, then redistributes funds via FAAC—turning states into supplicants. Rather than enabling subsidiaries to develop competitive advantages, it enforces operational uniformity and intervenes in local disputes. The parent company is doing middle management work.

The States (Strategic Business Units) should be semi-autonomous entities optimizing for regional contexts—Lagos as a commercial hub, Kano as an agro-industrial center, Rivers as an energy corridor. Nigerian states are cost centers instead. Most generate under 20% of operating budgets internally, depending on monthly FAAC allocations to meet payroll. There’s no penalty for underperformance and no reward for efficiency. Lagos subsidizes two dozen states with no governance rights in return.

Local Governments (Branch Operations) handle last-mile execution—waste management, primary healthcare, local roads. They’re the most anemic layer. States withhold statutory allocations, the HoldCo bypasses them with conditional grants, and many exist only on paper.

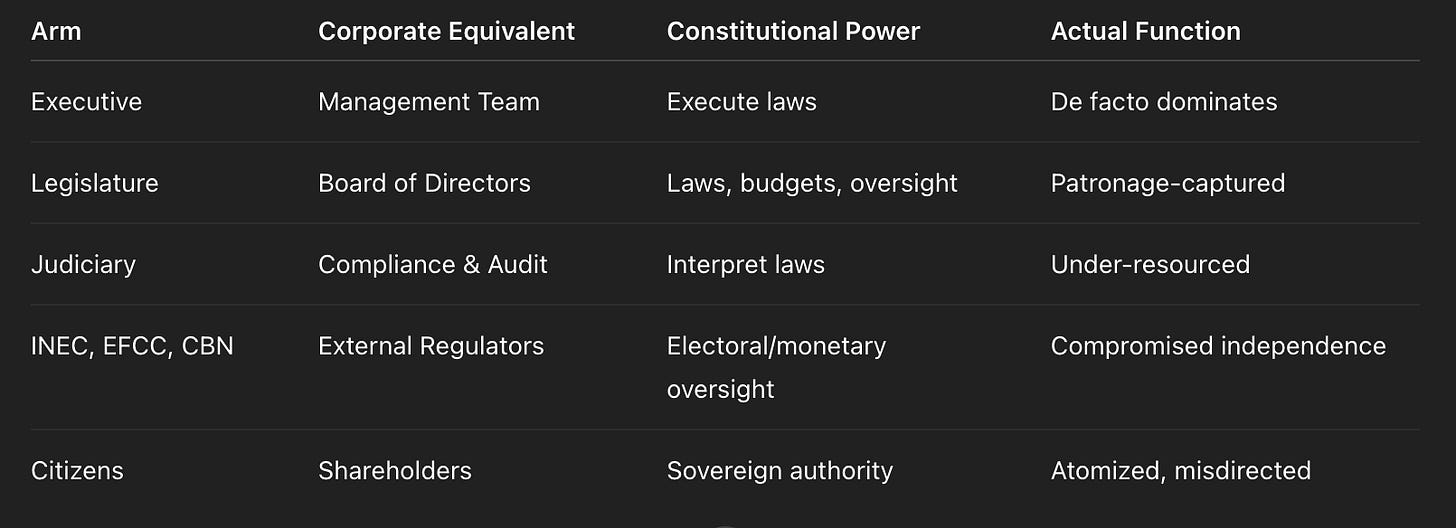

The Governance Map

The Broken Accountability Chain

In standard corporate structures, shareholders elect a Board, the Board appoints senior management through confirmation powers and structural control, and operational dismissals sit with the CEO and statutory HR bodies (civil service commissions). If the company underperforms, shareholders replace the Board, which replaces management.

Nigeria breaks this chain twice.

First, citizens directly elect both the Board (Legislature) and the CEO (President) in separate contests. This creates competing mandates. The President claims electoral legitimacy equal to the Legislature’s. The Legislature can’t fire the President except through impeachment—a quasi-judicial process requiring supermajorities, not a performance review. When things fail, each blames the other.

Second, Nigerian legislatures have been systematically captured through patronage. Committee assignments, constituency projects, and oversight budgets flow from the executive. The Board isn’t supervising management; it’s being compensated for non-interference.

The result: a governance structure that looks like separation of powers but functions like executive dominance with legislative decoration.

The Cultural Mismatch

Nigeria inherited republican architecture but monarchical instincts. Voters seek a sovereign to praise or blame, not a board to supervise.

Pre-colonial systems—the Oyo Alaafin checked by Oyomesi, the Benin Oba balanced by Uzama—concentrated visible sovereignty in one figure while embedding practical power-sharing in councils. Western republicanism evolved differently: power became visibly plural (parliaments) before operationally democratic. Nigeria grafted Westminster-Washington forms onto four centuries of governance psychology that identified authority with a person, not a process.

Citizens instinctively seek one leader to blame—the President as Oba, the Governor as Emir. The National Assembly passes budgets, confirms appointments, holds hearings. But this work happens in the cultural periphery, not where citizens direct emotional energy or accountability expectations.

Shareholder Rights and Misplaced Energy

Nigerian citizens hold three classes of voting rights: federal, state, and local. Corporate theory predicts tightest control at the subsidiary level, where information asymmetry is lowest and individual votes carry more weight.

Nigeria inverts this. Presidential elections are existential; local elections barely register. Shareholders obsess over the HoldCo AGM (where they have minimal direct influence) while skipping SBU AGMs (where they could directly remove underperforming management and scrutinize budgets).

This isn’t just cultural—it’s structurally induced by fiscal centralization. When the HoldCo controls 80% of revenue, subsidiary AGMs become theater. Why monitor your state assembly when it controls 15% of the budget with no autonomy over revenue generation?

Yet even at the federal level, focus is misdirected. Citizens fixate on who becomes President while ignoring what the President can actually do unilaterally versus what requires legislative approval. Most marquee acts require statutes or appropriations. Public discourse treats the President as if he holds monarchical decree power. When infrastructure decays, blame the President—never mind that the National Assembly cut the capital budget by 30%. When reforms stall, blame the President—overlook that the House blocked liberalization bills.

Legislators face almost no electoral accountability. How many Nigerians know their Senator’s committee assignments? How many have attended a constituency town hall? The Board operates in obscurity while shareholders rage at the CEO.

The Causal Chain of Dysfunction

Fiscal centralization (HoldCo monopolizes revenue) → dependent subsidiaries (states optimize for FAAC lobbying, not productivity) → captured boards (legislators trade oversight for patronage) → audit weakness (judiciary underfunded, regulators compromised) → inactive shareholders (rational apathy closes the loop).

What Functional Governance Looks Like

Performance-linked transfers: Base allocations guaranteed; growth capital earned through IGR, fiscal efficiency, and development outcomes.

Independent boards: Legislatures funded by statutory allocation, not executive goodwill. Auditor-Generals empowered to prosecute. Recall mechanisms triggered by citizen petitions.

Transparency as infrastructure: Treat budgets as annual reports. Publish quarterly accounts, dashboards, and legislative scorecards.

Subsidiary competition: Differentiate state strategies—Lagos for services, Abia for light manufacturing, Kano for agro-processing. Compete on productivity, not allocations.

Devolution with accountability: Direct local allocations, autonomous elections, legal standing to sue states that divert funds. Devolve power but tighten reporting.

The Bottom Line

When a company keeps blaming its CEO for every failure, it usually means the Board and shareholders stopped doing their jobs.

The Presidency is powerful but not omnipotent. The National Assembly controls budgets, appointments, and investigations. State Assemblies mirror this at the SBU level. Local councils—if empowered—could transform service delivery. But these institutions operate in shadows because citizens inherited governance psychology that seeks a king, not a board.

The 1979 Constitution deliberately fragmented power: federalism, bicameralism, independent agencies. But architecture doesn’t self-execute. It needs shareholders who read reports, track votes, demand briefings, and investigate budgets.

Nigeria won’t be fixed by a better CEO but by shareholders who govern the Board that governs the company. Vote, track, and replace legislators first; the executive follows.