The Quigley Layer: Africa’s Elite Turnover Is Already Underway

Credit channels are reorganizing faster than institutions can adapt. The next 15 years determine whether African states reconfigure deliberately or fracture under pressure.

Free Section

Africa’s political economy runs on two clocks.

The first is visible: elections, coups, debt restructurings, currency swings. This cycle dominates news flows and donor briefings. It moves quickly, generates noise, and encourages reactive interpretations.

The second clock moves slowly. It tracks institutional rigidity, elite circulation, and the credit architectures that determine who can mobilize resources and retain legitimacy. This is the clock that explains why long-stable regimes collapse abruptly, why new coalitions emerge with little warning, and why certain problems persist across multiple administrations.

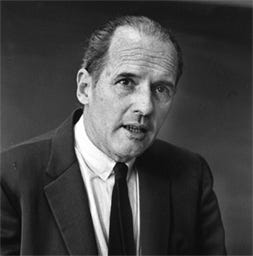

Carroll Quigley — the American historian who taught at Georgetown and consulted for the U.S. Department of Defense — spent decades studying long-cycle power dynamics. His students included Bill Clinton, who credited Quigley with shaping his understanding of how institutions rise, ossify, and reorganize. Members of Kennedy’s national security establishment also valued his work on civilizational resilience and elite circulation. His framework maps the progression from institutional creation to rigidity, decay, and reconfiguration. It offers a macro lens for understanding Africa’s trajectory between now and 2040.

Most analysis of African governance focuses on regime type, corruption indices, or democratic backsliding. These describe surface patterns. They don’t explain how elites lose legitimacy, how new power blocs form, or why post-independence arrangements struggle to absorb today’s economic and demographic pressures.

Africa is entering a reconfiguration window.

The structural indicators are clear. Median age under 20. Persistent youth unemployment even where GDP rises. Tight fiscal conditions across nearly every major economy. Rising debt service burdens. Currency instability becoming a fixed feature of macro management in Nigeria, Kenya, Ghana, Egypt, Ethiopia. Patronage networks — the stabilizing mechanism of elite bargains since independence — running into hard budget constraints.

Meanwhile, parallel power structures are consolidating. Diaspora networks shape capital flows and public narratives. Tech-enabled coordination lowers the cost of collective action. IP, cultural capital, and digital distribution generate new wealth outside state-dominated channels. Geopolitical competition expands the external leverage available to domestic actors.

The distance between incumbent elites and emerging selectors is widening. This is an institutional adaptability problem. Rigid systems weaken when economic capacity and legitimacy migrate to actors outside the traditional order.

Quigley’s key insight: power shifts when credit reorganizes. Not ideological credit — financial and social credit. Who can raise capital. Who commands trust. Who can coordinate meaningful action. Across the continent today, those channels are being rebuilt outside the structures that held since the 1960s.

The next 15 years will determine whether African states reconfigure through deliberate adaptation or through breakdown. The difference shapes market stability, institutional durability, and the cost of transition.

Understanding the Quigley Layer means recognizing that today’s political arrangements in Lagos, Nairobi, Accra, and Addis Ababa are late-phase structures. Replacement is not hypothetical. The live question is the mode of succession and who shapes it.

[Continue reading to access the full structural analysis, elite turnover mechanics, and strategic implications for founders, investors, and policymakers]