Three Paths Diverge: Venezuela, BRICS, and the Battle for Frontier Market Capital

How elite behavioral equilibrium determines whether African markets compound or dissipate under competing global scenarios—and why the positioning window closes H1 2026

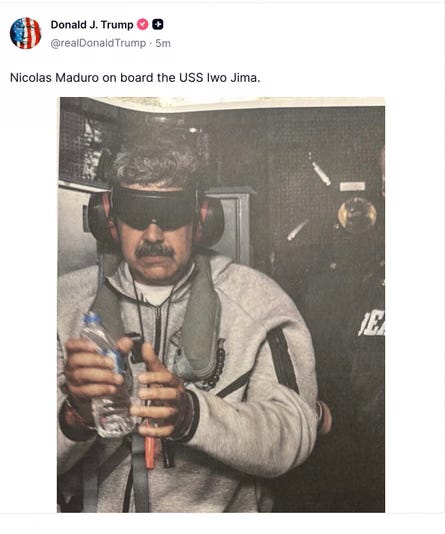

On January 3, 2026, the United States military seized control of Venezuelan oil infrastructure. Not in response to weapons programs. Not under humanitarian pretense. The official White House statement cited “economic security imperatives” and “domestic energy affordability objectives.” No coalition partners. No UN resolution. No attempt to obscure the action behind secondary justifications.

This isn’t the story that matters. The story is what three competing forces are now racing to achieve before mid-2026, and why African capital markets sit at the exact convergence point where these strategies either succeed or fracture.

Three visions compete for dominance over global resource flows, currency settlement architecture, and frontier market capital allocation. Each creates radically different outcomes for economies like Nigeria and Kenya. Understanding the transmission mechanisms—how oil prices translate to purchasing power, how payment rails determine trade patterns, how elite behavior converts surplus into either extraction or accumulation—matters more than predicting which vision wins. Position capital for structural divergence, not narrative convergence.

The Mar-a-Lago Strategy: Domestic Resurgence Through Resource Dominance

Scott Bessent’s “Three Arrows” framework targets 3% fiscal deficits, 3% real GDP growth, and an additional 3 million barrels per day of oil production. The strategy operates through denominator expansion: grow GDP faster than debt accumulates. Venezuela could potentially provide 1.5-2 million barrels daily — but it would take at least 18 months to get production back online, with repayment of US oil company legacy investments in Venezuela, and SPR replenishment being first priorities. Combined with Guyana expansion and sustained US shale output, oil remains at $60-70 per barrel by late 2027.

The domestic transmission runs through multiple channels. Lower oil means gasoline drops to $2.80-3.20 per gallon, adding $1,200-1,800 in annual household disposable income that flows into consumption. The Federal Reserve gains room to cut rates as inflation moderates. Housing affordability improves. AI investment booms—OpenAI, Anthropic, defence tech infrastructure—all requiring energy abundance at scale. Manufacturing re-shoring accelerates when paired with tariff policy. Rust belt job gains shift electoral maps.

Timeline pressure is explicit: November 2026 midterms demand visible wins. Voters need cheaper gas, rising wages, stock market gains. Venezuela delivers all three if execution holds.

But the surface strategy obscures deeper architecture. Venezuela seizure simultaneously denies China a Western Hemisphere oil supply agreement outside US naval chokepoint control. Greenland discussions target Arctic shipping lanes and rare earth deposits essential for Chinese semiconductor and battery supply chains. Panama signals that canal control matters if China-operated ports expand further. Recent Nigeria statements from Rubio, Hegseth and Bessent mark the Gulf of Guinea as contested sphere where the US won’t cede West African oil and gas access to Chinese infrastructure-for-resources deals.

Pattern recognition clarifies intent. Iraq in 2003, Libya in 2011, Venezuela in 2026—each denied China the ability to secure long-term energy agreements outside dollar-settlement frameworks and US naval dominance. The core objective is preventing Chinese dual-circulation autarky, where internal consumption combines with secured commodity imports to create economic self-sufficiency independent of Western financial architecture.

What makes this strategy unusual is the alignment: geopolitical containment and domestic political wins achieved through identical action. Most grand strategy imposes costs—military spending, sanctions-driven inflation, diplomatic friction. This generates benefits. Cheaper oil delivers electoral wins and undermines Chinese energy security simultaneously.

For African markets, the implication is structural. The US won’t “compete for Africa” with development aid or soft power. It will deny Chinese resource access through direct control where feasible or proxy pressure where geography limits direct action. Nigeria’s oil dependence makes it vulnerable to both dimensions: price suppression that collapses fiscal stability, and geopolitical pressure to reject Chinese infrastructure financing. Kenya, as net oil importer with no resource-curse exposure, benefits from cheaper energy and avoids getting trapped between great power competition over extraction rights.

If the strategy succeeds by Q3 2026—oil remaining below $70, inflation moderating, midterm gains—the model repeats. If it fails—oil rises above $85, inflation persists, electoral losses—Washington pivots toward accommodation or escalation. Either outcome reshapes African capital flows within months.

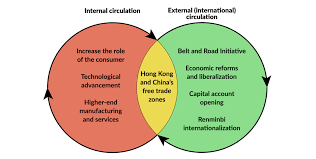

The BRICS Acceleration: Twenty Years of Plumbing, Six Months to Activate

BRICS isn’t coordinated central planning. It’s opportunistic pivoting by nations constructing alternatives to dollar-system dependence. The critical insight most analysis misses: this infrastructure has been building for two decades and is now reaching operational threshold.

The Cross-Border Interbank Payment System launched in 2015. It processed $13-14 trillion in 2025. If major commodity exporters—Saudi Arabia, UAE, potentially Nigeria—expand RMB settlement for oil transactions, CIPS could reach $20-25 trillion by late 2027. The New Development Bank (World Bank equivalent), established in 2014, has deployed $33 billion and targets $50 billion capacity. The Contingent Reserve Arrangement provides $100 billion in emergency liquidity, reducing IMF dependence. (Note that the capital bases of these organisations can be leveraged to access up to 10x additional funding.) The Shanghai Gold Exchange, internationalised in 2014, creates physical gold price-setting outside London Bullion Market Association control.

None of this is new. What changed is proximity to activation scale.

The settlement unit under development isn’t a “BRICS currency” in the traditional sense—no fixed convertibility, no central bank issuer. Instead, it’s a commodity-weighted basket: approximately 40% gold, 20% oil, 15% industrial metals, 15% agricultural commodities, 10% mixed reserve currencies including RMB. Think of it as creating money anchored to what countries actually produce and trade, not what central banks promise to redeem.

This matters because it breaks petrodollar recycling. If oil trades in commodity-weighted units instead of dollars, producing nations don’t automatically accumulate Treasury securities. Demand for US government debt falls. Interest rates rise structurally. The entire macroeconomic assumption underlying American fiscal expansion—that deficits don’t constrain policy because global demand for Treasuries remains infinite—fractures.

The threshold that makes this economically rational, not just politically motivated, sits in the eurodollar system. Foreign exchange swap spreads measure the cost of converting non-dollar assets into dollars. Normal conditions run -10 to -20 basis points. If eurodollar stress persists above -50 basis points for six to nine months—plausible under Mar-a-Lago fiscal expansion combined with geopolitical volatility—non-dollar settlement becomes cheaper for corporate treasurers. They shift for cost reasons, not ideology.

For African markets, BRICS infrastructure enables regional trade settlement without dollar intermediation. East African Community cross-border transactions currently lose 3-5% to currency conversion and correspondent banking fees. M-Pesa expansion across Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda combined with RMB settlement rails drops that to 0.8-1.2%. The savings compound. Ghana and Nigeria settling cocoa-for-manufactured-goods trade in commodity-weighted units instead of dollars eliminates Central Bank forex allocation bottlenecks that currently delay payments sometimes 6-9 months.

The challenge is execution versus capture. BRICS provides infrastructure. Whether African elites use it for trade efficiency or patronage distribution determines outcomes. Kenya’s M-Pesa adoption demonstrates institutional capacity for new payment rails. Nigeria’s history suggests forex allocation becomes another rent-extraction mechanism.

China’s Dual Circulation: Equity Conversions and the Venezuela Debt Test

China’s dual circulation strategy separates internal consumption growth—targeting 60%+ of GDP—from external commodity security. Belt and Road Initiative 2.0 reflects this shift through debt-to-equity conversions. Approximately 15-25% of African BRI debt portfolios are converting to equity stakes in railways, ports, and energy projects.

This changes completion incentives fundamentally. Under pure debt financing, Chinese lenders profit whether the railway operates or sits incomplete—repayment occurs regardless of functionality. Under equity conversion, Chinese returns depend on actual cargo volumes, passenger traffic, operational revenue. A non-functional railway generates zero equity returns. This aligns Chinese institutional interests with project completion and long-term operational success.

African infrastructure completion rates historically run 40-50% under debt-only financing. Equity-conversion trigger events will likely also increase as a number of these loans become distressed. Early evidence from equity-converted projects in Kenya and Ethiopia suggests 70-80% completion rates. The difference compounds over decades.

But Venezuela presents an immediate test case that will determine Chinese credibility across all frontier markets. China holds over $20 billion in Venezuelan debt, structured as oil-backed loans issued between 2008 and 2016. US seizure of Venezuelan oil infrastructure makes that debt unrecoverable unless China provides military or financial counter-support to Caracas.

The choice is binary. Defend Venezuelan sovereignty—proving BRICS mutual-defense credibility and willingness to challenge dollar-system enforcement—or write off $20 billion and signal that when dollar-system pressure intensifies, Chinese support evaporates. African governments considering long-term infrastructure partnerships are watching. If China abandons Venezuela, why would Nigeria or Kenya trust 30-year railway financing agreements?

Watch for PBOC swap lines to Caracas in February-March 2026. If they materialize with sufficient scale—$8-12 billion—China signals commitment. If they don’t, the implicit message is that BRICS provides opportunistic benefits but no reliable counter-framework when American enforcement reaches critical intensity.

For African markets, China’s commodity demand under dual circulation sustains oil at $95-115 notwithstanding Mar-a-Lago-desired increase in Western Hemisphere supply. Its internal consumption growth requires energy security. But the Venezuela test determines whether African governments can rely on Chinese financing as a genuine alternative or merely as negotiating leverage against Western conditional lending.

The Nigeria-Kenya Divergence: Why Structure Determines Outcome

Most “Africa exposure” treats the continent as homogeneous risk. The three competing scenarios reveal structural divergence that makes this assumption catastrophically expensive.

Nigeria and Kenya sit at opposite ends of a spectrum determining whether surplus converts into compounding wealth or dissipates into extraction. The difference isn’t GDP growth rates or demographic dividends. It’s how elite behavioral equilibria interact with external shocks.

Nigeria Under Three Scenarios

Under Mar-a-Lago, oil persistence at $60-70 per barrel triggers immediate fiscal crisis. Nigeria’s budget breakeven sits around $70. Federal allocations to states collapse. Wage arrears spread. The naira moves from ₦1,500 to ₦1,750-1,900 by Q3 2026.

Effective Economic Total Addressable Market—the population subset that is economically active, digitally connected, able to afford non-essential purchases, and transacting with sufficient frequency to matter for venture-backed business models—contracts from approximately $3.1 billion to $2.6 billion. That’s 16% reduction in the actual market fintechs, e-commerce platforms, and consumer services can monetize. Population doesn’t change. Addressability does.

Consumer fintech valuations priced at 5-8× revenue face structural revaluation when the denominator shrinks 16% and customer acquisition costs rise as disposable income falls. This isn’t sentiment shift. It’s balance sheet mathematics.

Under BRICS scenarios, outcomes bifurcate based on execution. If Nigeria successfully implements oil-for-RMB settlement paired with Central Bank naira-RMB swap lines, the currency stabilizes at ₦1,200-1,350. EETAM expands roughly 16%. But execution requires institutional capacity Nigeria hasn’t demonstrated. The more probable path—elite capture of RMB allocation creating new rent-extraction mechanisms without meaningful reforms—leaves the naira at ₦1,400-1,550 and EETAM down 3%. Weighting these sub-scenarios suggests expected EETAM growth of approximately 5%. Modest. Unreliable.

Under China Build, where BRI 2.0 debt-to-equity conversions combine with sustained oil demand at $95-115, EETAM could expand 39%. Infrastructure completion drives logistics cost reductions. Higher oil revenue stabilises fiscal transfers. But this scenario assumes elite behaviour inconsistent with observable patterns.

Kenya Under Three Scenarios

Kenya’s outcomes cluster positively across all three visions because structural position differs fundamentally.

Under Mar-a-Lago, oil at $60-70 reduces Kenya’s import bill from approximately $4.5 billion annually to $3 billion. That $1.5 billion savings represents roughly 2% of GDP flowing directly into fiscal relief and private sector liquidity. EETAM expands approximately 18%.

Under BRICS, East African Community regional trade combined with M-Pesa cross-border expansion captures non-dollar settlement efficiency gains. EETAM grows roughly 27%.

Under China Build, Standard Gauge Railway completion to Uganda border paired with Mombasa Special Economic Zone activation generates logistics cost reductions and manufacturing activity increases. EETAM expands approximately 36%.

Kenya benefits as net oil importer where Nigeria suffers as exporter. Kenya’s M-Pesa digital ecosystem operates at 83% adoption versus Nigeria’s 61%, meaning efficiency gains from new payment rails translate faster into transaction volume increases. But the critical variable isn’t infrastructure or technology.

The Elite Behavioral Equilibrium

Nairobi demonstrates capital accumulation equilibrium—wealth compounds locally through tech ecosystem investment, real estate development, and regional corporate headquarters establishment. Nigerian elites demonstrate extraction equilibrium—wealth dissipates offshore into London property, Miami real estate, patronage distribution.

The pattern has historical precedent. Nigeria’s 2005-2014 oil boom at $100-120 per barrel generated massive revenues. EETAM grew slower than population. Elite extraction dominated. Wealth vanished into overseas accounts and luxury consumption. Infrastructure investment remained minimal outside Lagos corridor.

Kenya’s 2010-2020 period showed lower GDP growth and no commodity windfall. EETAM grew faster than population. The M-Pesa ecosystem expanded. Nairobi real estate compounded. Regional corporate activity increased. Partial elite accumulation within functional enclave.

Kenya’s structural advantage isn’t better governance in abstract. It’s that the elite accumulation equilibrium already established in Nairobi persists across scenarios and potentially strengthens as Nigerian capital likely seeks non-dollar repositioning options within Africa.

The question becomes what psychological effect the Venezuela incident will have on Nigerian elites.

The Venezuela Effect on Elite Behaviour: Enforcement Reach, Not Intervention Fear

The overlooked transmission mechanism from Venezuela to African capital markets operates through elite observation, not military threat assessment.

Nigeria faces no US strategic interest comparable to Venezuela. No military seizure risk. But Venezuela matters because it demonstrates dollar-system enforcement reach when American political calculus shifts.

Venezuelan elites holding US bank accounts, London property, and Miami real estate faced comprehensive asset freezes before military action. Decades of accumulated wealth became inaccessible overnight. The enforcement preceded the seizure. The legal justification—“economic security imperatives”—established a precedent with no limiting principle.

Nigerian elites observing this pattern draw rational conclusions. If the United States will seize sovereign Venezuelan oil assets explicitly for domestic economic objectives, enforcement against individual wealth held in dollar-system jurisdictions becomes trivial by comparison. The question isn’t whether American military forces will operate in Lagos. The question is whether assets accumulated in London, New York, or Miami remain secure when American political priorities shift.

Venezuela accelerates Nigeria’s divergence from the Kenyan pattern. Even optimistic scenarios projecting EETAM growth assume elite behavioral equilibria inconsistent with post-Venezuela incentives. Those projections require that oil revenue surplus or Chinese infrastructure investment translates into domestic business ecosystem expansion and consumer purchasing power increases.

But if Nigerian elites extract windfalls immediately and offshore aggressively to non-dollar jurisdictions, the causal mechanisms driving EETAM expansion fail before materializing. Infrastructure investment doesn’t happen because capital leaves before projects get financed. Business scaling stalls because working capital flows offshore rather than into inventory, hiring, or market expansion.

The rational repositioning pattern—accelerated movement toward Dubai, Singapore, Nairobi—reflects updated risk assessment. Dollar-system enforcement demonstrated reach beyond legal frameworks when political imperatives aligned. Wealth accumulated in those jurisdictions no longer appears secure across multi-decade timeframes that matter for generational asset preservation.

This creates the investment implication: Nigeria becomes uninvestable at current consumer fintech valuations—5-8× revenue multiples—unless elite behavioral shift toward accumulation materializes and sustains. The Tinubu administration’s Lagos precedent and recent domestic capital deployment by Dangote, Otedola, and Rabiu suggest this shift is possible. Tinubu’s 1999-2007 governorship established Lekki Free Zone foundations, initiated Eko Atlantic, and built BRT infrastructure. Dangote committed $19 billion to the refinery. Otedola previously acquired Geregu Power (recently divested to another member of the local elite). Rabiu expanded BUA Cement capacity domestically, and is on course to establish a competing domestic refinery to Dangote.

But Venezuela raises the stakes. If these elites conclude that even domestic accumulation faces enforcement risk when routed through dollar-system touchpoints—correspondent banking, trade finance, equipment imports—the behavioral shift aborts before compounding begins.

Nigeria requires evidence of sustained elite accumulation measured through infrastructure completion rates, domestic reinvestment ratios, and reduced offshore wealth flows before valuations reflect optimistic scenarios. That evidence takes 12-18 months to confirm. Kenya’s accumulation equilibrium already exists and demonstrates resilience across scenarios.

What This Means for Capital Allocation

Three investment truths emerge from scenario analysis combined with elite behavioral mechanics.

First: Nigeria operates as high-risk, scenario-dependent asset requiring elite behavioral confirmation. Expected EETAM outcomes range from -16% under Mar-a-Lago to +39% under China Build, but current valuations price in optimistic scenarios without evidence that elite accumulation equilibrium will sustain. Dangote, Otedola, and Rabiu deploying more capital domestically signals possibility. Venezuela raising enforcement stakes creates counterforce. The asset requires 12-18 months of behavioral confirmation—infrastructure completion, domestic reinvestment persistence, reduced offshore flows—before multiples justify scenarios already priced in. Until then, volatility dominates compounding.

Second: Kenya functions as quality compounder across all scenarios. Expected EETAM growth ranges from +18% under Mar-a-Lago to +36% under China Build. Kenya benefits from oil price suppression where Nigeria suffers. Regional trade expansion under BRICS scenarios captures efficiency gains from non-dollar settlement rails that Nigeria’s institutional weakness prevents from materializing. The elite accumulation equilibrium established in Nairobi supports sustained growth regardless of which external scenario dominates.

Third: Timeline compression creates narrow positioning window. Venezuela compresses scenario clarity to mid-2026. Mar-a-Lago either delivers visible oil price drops and midterm wins by November 2026, or the strategy pivots. BRICS activation becomes clear if major commodity exporters announce RMB settlement frameworks in H1 2026. China’s Venezuela decision materializes through PBOC swap line actions in Q1-Q2 2026.

But strategic direction and economic outcome operate on different timeframes. Actual transmission—fiscal adjustments, consumer purchasing power changes, infrastructure completion—unfolds through 2027. Capital positioned in H1 2026 captures repricing as outcomes materialize. Capital waiting until economic effects become fully evident in late 2027 deploys 12-18 months late at valuations that already reflect the new reality.

The broader pattern extends beyond Nigeria and Kenya. Frontier markets where elite behavioral equilibria favor accumulation over extraction will compound capital regardless of which global scenario dominates. Markets where extraction equilibria dominate will generate activity—transaction volume, headline growth, fundraising announcements—without wealth accumulation for outside investors.

Venezuela didn’t just reveal American willingness to seize resources for explicit economic objectives. It revealed the enforcement architecture underlying dollar-system stability and compressed investment decision timelines from comfortable multi-year horizons to uncomfortable quarters where strategic clarity emerges before economic confirmation arrives.

Closing

Three forces compete for dominance over global capital flows. Mar-a-Lago pursues domestic resurgence through resource control that simultaneously denies Chinese commodity security. BRICS activates two decades of payment infrastructure construction, creating alternatives to dollar settlement when eurodollar stress makes switching economically rational. China aligns completion incentives through equity conversions while testing its commitment to mutual defense through Venezuela response.

By mid-to-late 2026, strategic direction becomes clear. Economic outcomes unfold through 2027.

For African markets, the question isn’t which scenario prevails. The question is which economies demonstrate structural capacity to convert external surplus—whether from cheaper oil, Chinese infrastructure, or regional trade expansion—into compounding domestic wealth rather than offshore extraction.

Nigeria and Kenya sit at opposite ends of this spectrum. Most analysis treats them as comparable frontier market exposures differentiated by size and sector mix. The structural difference is elite behavioral equilibrium. Nairobi demonstrates capital accumulation. Lagos demonstrates extraction with possible inflection toward accumulation that requires 12-18 months to confirm.

Venezuela compressed the timeline by revealing enforcement architecture reach and raising the stakes for elite wealth positioned in dollar-system jurisdictions. The seizure wasn’t just about American oil supply. It demonstrated that sovereignty subordinates to American economic imperatives when domestic political calculus aligns, and that enforcement precedes action.

Capital positioned for structural divergence compounds. Capital positioned for narrative convergence dissipates.

The paths have diverged. The positioning window is H1 2026. The outcomes materialize through 2027.

For institutional EETAM analysis, scenario modeling, or frontier market structuring: lumi@lumimustapha.com