WHAT DOES MUSIC PUBLISHING MEAN IN NIGERIA?

Music publishing in Nigeria is a barren landscape. However, there are now green shoots of growth dotted around the terrain. These isolated…

Music publishing in Nigeria is a barren landscape. However, there are now green shoots of growth dotted around the terrain. These isolated successes, like ripples in water, will hopefully spread and eventually connect to create a viable foundational sub-sector within the Nigerian recorded music industry.

The growth in popularity of Afrobeats music over the past 18 months have shown why it has never been a more important time for the Nigerian music publishing sector to get its act in order and ensure the material benefits our intellectual property generate are enjoyed by its local creators.

In the UK Afrobeats/Afroswing is mainstream pop music meaning songs in these genres have enjoyed hundreds of thousands of radio spins, hundreds of millions of streams, and a lot of (user generated/premium) synchronizations. All of which mean that a lot of money has already been generated and has accrued from Nigerian music in the UK. The question becomes whether the Nigerian creators of these works have been getting paid?

Why Music Publishing Matters

Composers, songwriters and music publishers only have one asset to trade. And that is the music itself. That is their only source of revenue within the business. As such, music publishing related revenues are the single most important return a songwriter/instrumental composer (or their publisher) can make. Imagine songs as the raw material input required for artists/labels to produce the recordings which they retail to consumers, and (more importantly) leverage for other commercial benefits.

Music publishing revenues are roughly just below half of the overall value of recorded music. Mechanical royalties specifically, however — i.e. the publishing share of sales, downloads and streams — are an even smaller fraction of the royalties paid for sound recordings. The average music publishing rate (or cut) from on-demand streaming is roughly 15%. On the face of it this might seem negligible, but this is just one stream of income.

Global recorded music revenues in 2018 amounted to just over $19b. Music publishing revenues for the same period were around $5.5b; $3.3b from the US market (which accounts for over half of global revenues), and an estimated $2.3b from the rest of the world. This is a 55% growth over a five-year period — as compared with the 36% growth in sound recording revenues.

Music publishing revenues are also more diverse than recording income. Whilst digital streaming is undoubtedly a growth centre, only 36% of total publishing revenues come from this source; in contrast with labels/artists whose streaming income accounts for 80%+ of their overall recording revenues. When the earlier mentioned $5.5b of publishers revenues are added with the over $8b in performance rights organisations (PROs) collection revenues (collected on behalf of publishers and composers), one can begin to understand why music publishing is increasingly viewed as an appreciating asset class.

Now let’s take a closer look at what’s going on at home.

Current Nigerian Landscape

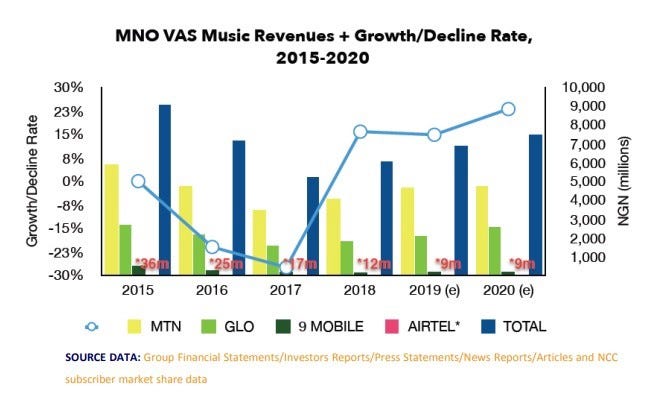

According to the Disruptive Creative Economy Meeting group’s “Nigerian Recorded Music Industry Report, 2019” the value of the Nigerian recorded music business is estimated at $45m and expected to grow to $50m by the end of this year. Note that these figures are based on domestic consumption and will over time be increasingly bolstered by revenues from foreign territories. Based on these current figures, and the average global ratio of sound recording to (mechanical) music publishing revenues, the value of Nigeria’s domestic music publishing industry can be estimated to be somewhere in the region of $6–7m (circa N2.5b).

This may seem negligible to some, particularly when (misguidedly) compared to more advanced markets, but it is significant when properly considered. Firstly, music publishing income is extremely high margin compared to sound recording revenues. Recording revenues must first absorb the costs associated with the marketing, promotion, production of videos/live shows related to the recordings, before they result in profit (if any). This is why back catalogue revenues are regarded as the primary means through which labels can consistently invest in newer frontline catalogue development/acquisition.

Such is not the case with music publishing revenues. This type of income, being passive (unencumbered) income from the beginning, is extremely high margin and periodic, almost like an annuity — and for the lifetime of the composer plus 70 years. It is so steady an income source that major investment funds/houses are now ploughing huge investments into music publishing repertoires and paying 5–6x+ above the average annual income of the copyrights.

One has to also appreciate the importance of music publishing income as the backbone upon which all those that are involved in the creation/supply side of the business are rewarded for their creativity — and thus encouraged to create more. Nigerian music is now firmly on the global radar and, consequently, the local music publishing sector industry must be properly positioned to capitalize on its exploitation

Nigerian Music Publishers

Whilst the local digital music revolution has been ongoing, composers, songwriters and music publishers have been quietly getting their houses in order. Documentation of rights, registration and formal licensing are the background, non-glamorous, but crucial activities that have been (and are currently being) undertaken. Successfully achieving these objectives now allows the owners of Nigerian songs to collect and receive the accrued revenues their works have generated not just domestically but all over the world.

In 2017 some of the major Nigerian publishers formed the Music Publishers Association of Nigeria (MPAN). This body has been the vehicle through which local music publishers have been collectively interacting with the key players in the Nigerian music copyright sector. Players such as music companies, PROs, the Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC) and international partners. As it stands its members include Universal Music Nigeria, Replete Publishing (Chocolate City), Premier Music, Hypertek Digital (2Face, Burna Boy), and Green Light Music Publishing (Del B, Fliptyce, Chopstix, Tony Ross, Tee-Y Mix).

For the first time, a large collection of hit Nigerian songs have being catalogued, registered, and are now being administered both locally and internationally. Prior to this, and despite the huge splash Afrobeats music has been making around the world, almost none of the music-related revenue generated has flowed back to its rightful local owners.

The primary reason? Almost none of the songs, nor their composers/publishers, had been registered with the appropriate bodies. So, in some cases, money has accrued but is yet to be paid. And in other cases — where some have unscrupulously registered the works in their own names — money has accrued and been paid, but not to the rightful owners. A lack of accurate metadata, split sheets, and international standard works codes (ISWCs) for Nigerian songs are but a few of the challenges that have been/are being faced.

Resolving these respective issues have been the primary activities of serious Nigerian publishers till date. Some are entering into partnerships with their more advanced international peers to market, licence, administer Nigerian songs globally (save for Africa — where local publishers do it themselves) in order to speed up revenue streams and reduce the costs of having that revenue pass through multiple PROs before being remitted to COSON for payment to owners. Others are utilising administrators to try and clawback some possibly already accrued micro-payments here and there for some quick money.

Despite all these developments, local PROs continue to struggle with royalty payments to their members. Internationally, performance royalties are the single largest source of revenues for music composers/publishers and they are generally administered collectively by/through these PROs; hence, the importance of developing our local equivalents and contributing to their growth as they will play a key role if our nascent music publishing industry is to truly grow.

Local Performance Rights Organisations?

Despite several legal battles, some of which are ongoing, there are currently two PROs in Nigeria. The Copyright Society of Nigeria Gte/Ltd (COSON) and the Music Copyright Society of Nigeria Gte/Ltd (MCSN). COSON, being the leading PRO, has made great strides in terms of its licensing and collection activities, but has also suffered a lot of difficulties (and criticisms) regarding its payment, or lack thereof, of collected royalties. MCSN, whilst having the occasional successes, has generally struggled to grow and attract new members.

COSON’s primary victory has been the recognition of music copyrights by commercial music users (such as broadcasters, telcos, hotels etc) and then said users paying for the music they were using. This achievement cannot be overstated given the traditional culture in the country of seeing/treating music as not having any inherent value — and more or less “communal property” (like with folklore). COSON’s success in this regard saw revenues collected by the organisation grow from zero to almost $1m over a few years. Not yet enough to get on the CISAC Global Collections Report, but growing fast.

Progress has been slowed, however, by severe internal conflicts which have had a detrimental effect on the organisation’s collection rates, working capital and general operational activities. Board coups, counter coups, law suits, criminal petitions, regulatory sanctions and a PR war has culminated in COSON’s operational licence being suspended by the NCC and it’s bank accounts frozen for a period. Collections have ground to a halt and operational activities have severely suffered.

More interestingly, and despite the clear provisions of Nigerian copyright law, COSON initially only recognised the copyrights of sound recording owners and not of the composers/songwriters and publishers of the underlying songs in the recordings. The prevailing view at the time from the PROs (and some music label heads) was that songs were part of the recordings and that the artists and labels were the owners of both sets of copyrights. Extensive discussions, and education, ensued — with the PROs seeking international advice — until all finally came to understand.

With this realisation, attention turned towards the earlier mentioned major commercial users of music; e.g. the telcos, the broadcasters, large hotels etc. The PROs, understanding that they had only been licensing rights related sound recordings, have now begun (along with MPAN) to engage with these users on their current licence rates, which now have to accommodate and compensate another class of rights-holders. A number are now complying, whilst some are yet to.

Once this battle is won, hopefully by amicable resolution (but if not by litigation), then the final front will be the review of the rates currently paid for music copyrights in the country; which are pitiful by any standards not to talk of international ones. The current rates paid by, for example, broadcasters are a fixed fee between $8k &$10k per year for the hundreds if not thousands of songs they play annually. This is as opposed to them paying a percentage of their revenues, which is the standard practice. But one battle at a time.

For the moment, sights are set on working with COSON to digitize its activities — in terms of registration of members’ works and members’ details, and uploading/synchronizing that information to/with the CISAC-powered global music copyright information database CIS-NET. That way at least all monies generated by Nigerian works globally will accrue to the rightful owners — even if there may still be one or two payment issues once remitted to our local PROs.

Conclusion

The foregoing is just a glimpse into the current shape of the music publishing landscape in Nigeria. Considering the industry was effectively starting from scratch just a few years ago, tremendous progress has been made to get to where it is now. Recognition of copyrights in musical compositions/songs was the first step. The PROs were made to recognise them and they in turn worked with music publishers to make labels and the commercial users also understand.

The next step is for publishing royalties to be paid on a regular basis to composers/publishers based on the usage of their works and in a seamless digitally efficient manner. Some members of MPAN are currently in court with COSON on this very issue.

Once this has been achieved attention can then be turned towards the next most pressing issue; namely, the upward revision of licensing rates (for mechanical and performance rights) which will require an industry wide consensus and common position in order to attain the leverage necessary to “convince” major commercial music users (both locally and internationally) into agreeing. So important is this topic that it will be addressed in more detail in a coming post.

In the meantime, the sky is only the beginning for the Nigerian music publishing sector.